Selection of children according to the rules // The Supreme Court for the first time clarified the old norms of the Family Code

Today, the Plenum of the Supreme Court (SC) adopted a resolution on the protection of children in the event of a threat to their life and health, deprivation and limitation of parental rights. In the final version, some provisions of the draft were softened. For example, parental rights can be deprived for preventing a child from receiving not just any education, but general education, i.e. for not allowing the child to go to school. To urgently remove a child from adults if his life and health are threatened, a preliminary decision of the authorized body will be required. The project proposed to agree with the current practice, when in some cases a child is removed from the family even before such a decision is made.

The issues resolved by the Supreme Court in its resolution attracted public attention. Reacting to the discussion and appeals received by the court, the developers at the last moment adjusted the clause on what is meant by abuse of parental rights. According to the project, parental rights could be deprived for “creating obstacles to education.” This general formulation was replaced by a more specific one - “creating obstacles to obtaining... general education.” In other words, parental rights can be deprived of those parents who do not allow their children to go to school. The corrected version of the paragraph was included in the materials of the plenum on a separate sheet. However, another clarification remained unchanged, according to which one of the grounds for deprivation of parental rights may be lack of concern for the child’s education (subparagraph “a”, paragraph 16 of the resolution).

However, this discussion point probably creates few problems for parents in practice. The Chairman of the Supreme Court Judicial Panel for Family Disputes, Alexander Klikushin, speaking with journalists, noted that he is not aware of cases of deprivation of parental rights due to the fact that the parents did not allow the child to receive an education.

For the first time, the plenum decided to clarify how guardianship authorities can remove children from their families without a court decision in the event of a threat to their life and health. This norm (Article 77) has been in the Family Code since its adoption in 1994. It was formulated, however, in a very general form, which is why it was applied in different ways “on the ground,” noted Alexander Klikushin.

For example, in practice, guardianship authorities can take away a child even before the executive body of the subject or the head of the municipality adopts a special act on this, as required by Art. 77 SK. Then a document on seizure is drawn up, and the act is accepted later, explained Alexander Klikushin. The draft resolution recognized this practice as acceptable. However, in the final version they abandoned this, deciding to follow the letter of the law.

The developers tried to describe the grounds for the emergency removal of a child as conservatively as possible. An immediate threat to the life and health of a child is proposed to be understood as “a threat that clearly indicates a real possibility of negative consequences in the form of death, harm to the physical or mental health of the child” (paragraph 28). The situation can arise both as a result of the active actions of parents and guardians, and as a result of their inaction, when they, for example, do not prevent third parties (neighbors, etc.) from harming the child (clause 34). Moreover, the difficult financial situation of the family cannot be a basis for removing a child, provided that he is taken care of “in accordance with available... capabilities” (paragraph 33).

However, it seems that the guardianship authorities are in no hurry to abuse the powers granted by Art. 77 SK. According to Alexander Klikushin, over the past year about 3.4 thousand such acts were adopted, and several dozen of them were appealed, and only about 20 complaints were successful. He suggested that the rare cases of appeals against acts of removal of children are associated with the virtual absence of rules governing this procedure. It is possible, however, that the persons from whom the children were taken were not themselves interested in returning them.

Deprivation of parental rights. Commentary on the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court

On November 14, 2021, the Supreme Court adopted the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court, in which it once again considered issues related to deprivation of parental rights. This Resolution was not a revolution, but it must be said that any Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court never changes the legislation. It only talks about how exactly to apply the current legislation that already exists at the moment. In addition, the Supreme Court has repeatedly explained with the same material, with the same Family Code, how to apply the law when depriving parental rights. But this time, rule-making took a more correct path; the Supreme Court began to tell lower courts how to apply this legislation, literally laying out exactly how this is done. In my opinion, the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court is quite interesting for commentary, and I will allow myself to comment on several provisions.

Clarifications of the Supreme Court

First of all, it should be noted that the Supreme Court allowed (now what is already called “from above”) to apply legislation by analogy when limiting the parental rights of adoptive parents

. That is, before there was a conversation that adoptive parents could only lose parental rights, that is, completely cancel the adoption; there was no other option for those adoptive parents who had trouble and could not care for their children as they should. They could only cancel the adoption. This is analogous to deprivation of parental rights.

And now, the Supreme Court said, restriction of parental rights can be applied by analogy, that is, in my opinion, this is a more progressive approach. Indeed, sometimes circumstances arise when the adoptive parent cannot, for various reasons, continue to exercise his parental rights, but there seems to be no reason to deprive him of parental rights. Under such circumstances, it will be possible to limit his parental rights. The only story is that the Supreme Court did not go all the way in this analogy and did not tell, for example, what to do with restoring the parental rights of adoptive parents, whether this can be done. If the adoption was cancelled, is it possible to return everything back? The Supreme Court did not indicate this point in this Resolution.

Other Resolutions say quite clearly and understandably - and this, in fact, follows directly from the law - the cancellation of adoption, unfortunately, is a one-sided process. Once the adoption has been cancelled, it is no longer possible to restore it.

The second point that attracts attention: the Supreme Court indicated that when limiting parental rights, it is impossible to indicate the period for which such a restriction is introduced

. Previously, there were frequent decisions when a restriction was introduced for a certain period, for example, parental rights were limited for 6 months or a year. The Supreme Court quite rightly pointed out that the restriction of parental rights is not a period of time, but a ray (there is a beginning, but no end). The Supreme Court correctly indicated that when limiting parental rights, a period cannot be set, that is, it begins and ends with one of two things: either parental rights will be restored, or parental rights will be permanently deprived. But nothing happens automatically. Six months have passed or any other period, but parental rights continue to be limited.

When filing a lawsuit for deprivation of parental rights, the Supreme Court described in detail who can do this, and once again explained that persons acting in place of parents are guardians, adoptive parents, trustees, foster parents, and foster carers. That is, all those persons who, by virtue of the law, are the legal representatives of the child, and not just those persons who have custody of the child in the everyday sense. If a child in the everyday sense, for example, is in the care of his aunt, this does not mean that the aunt has the right to file for deprivation of parental rights. When the aunt is appointed guardian, then it will be possible to raise the question.

Grounds for deprivation of parental rights

If we take specific grounds for deprivation of parental rights, there are only a few of them. Art. 69 of the Family Code has not undergone any significant changes, and the Supreme Court went through all these grounds in detail.

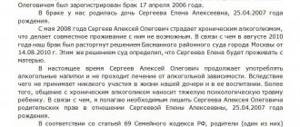

One of the main, most “popular” grounds for deprivation of parental rights is malicious evasion of child support payments.

. The court once again explained that evasion of payment of alimony can only occur if this alimony is paid by a court decision or by a notarized agreement between the parents. If alimony is not paid simply, then in this case, unfortunately, it is impossible to say that there is a malicious failure to pay alimony.

But at the same time, the court went further and explained what malicious non-payment of alimony is. Previously, there was a point of view and it was reflected in the documents of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation that malicious evasion of alimony payment is when there is a criminal case for evasion of alimony payment. Only in this case. No, not only!

The Supreme Court, drawing attention to the fact that evasion of alimony payments must be malicious, says that not only the bailiff’s decision to prosecute for evasion of alimony payments can be the basis for such a claim, but also some other circumstances. In particular, the mere presence of arrears in the payment of alimony may already indicate that a person is maliciously evading their payment, regardless of whether he is held accountable or not. Also, concealment by the debtor of earnings or other income is also evasion; searching for a parent obligated to pay child support due to his concealment of his whereabouts; bringing a parent (already as one of the options) to administrative or criminal liability for failure to pay funds for the maintenance of a minor child.

This is truly a breakthrough. Previously, the mere presence of debt was not a basis for deprivation of parental rights. It was imperative to get the bailiffs to hold the debtor accountable, which was associated with significant difficulties. However, the mere presence of debt is not a strict automatic basis for deprivation of parental rights. The court must take into account the duration and reasons for the parent's failure to pay child support, that is, this is a matter that requires evidence. The mere existence of debt is not a reason.

If we take practice, the presence of debt always adds arguments when depriving parental rights, especially since we usually observe that the second parent did not communicate with the child for a long time, did not participate in his life in any way, and did not pay child support. In this case, this story will be taken into account, but now the court must enter into a discussion: why did the second parent not pay child support, maybe he had some objective reasons and grounds for this.

The grounds provided for in paragraph. 3 tbsp. 69 of the Family Code, namely when parents refuse to take their child from the organization without good reason

, Where is he located. Usually this did not require any explanation, but was rare enough to be used in the lives of citizens. Typically, such applications were submitted by organizations for children left without parental care, for example, when a child is in a child’s home, and his parents do not come and do not pick up the child. This was the basis for deprivation of parental rights. Now the Supreme Court once again emphasized that when considering this case, the judge must find out what were the reasons for the refusal to take the child from the organization for children left without parental care. And if these reasons were valid, then deny the deprivation of parental rights.

Another point that requires close attention. The Supreme Court indicated to the lower judges that they must enter into a discussion of another issue - whether the parents had a reason in principle to place the child in the orphanage.

After all, the situation often happens that a single mother placed her child in an orphanage, does not come for some time, and the question of depriving her of parental rights is raised. Here the court was asked to raise the question of whether she had grounds for placing the child in an orphanage? After all, this is not a storage room; you cannot arbitrarily bring a child there and leave him to live there, because the mother simply does not want to raise him. There must be certain reasons, for example, a difficult financial situation. Now the court must examine these circumstances when deciding the issue of deprivation of parental rights, which, in my opinion, is fair and correct. The court must also check whether the relationship between the parent and the child is maintained, and other circumstances that were previously clarified, but here they are set out in more detail and fully. I hope this will lead to more correct law enforcement practice, when judges will act uniformly in this situation, because there were often cases when, without any evidence at all, parents were deprived of parental rights in relation to children who were in the child’s home. This is on the one hand. On the other hand, they called the child’s mother, who had already forgotten what her child looked like, a hundred times to find out what the reasons were. A balance needs to be found here, and the Supreme Court is trying to find this balance in its ruling.

There is one of the grounds for deprivation of parental rights - abuse of parental rights

. The court explains that not any abuse of parental rights is grounds for deprivation of parental rights. For example, abuse of parental rights will include creating obstacles in education, involvement in gambling, inducing vagrancy, involvement in the activities of organizations banned in the Russian Federation, etc. This more detailed, clearer explanation is actually necessary for the courts, because in our country anything and everything has been dragged under the abuse of parental rights. For example, if you didn’t agree to travel abroad, that’s all, abuse. This is wrong. There really must be an abuse of parental rights to harm the child. In this case, the Supreme Court describes this situation in more detail, allowing lower courts to more competently apply the law.

The last one listed in Art. 69 of the Family Code, the basis for deprivation of parental rights is the commission of an intentional crime against the life and health of the spouse or the second parent of the child

. In this case, the Court clarified - although in my opinion it was obvious, but law enforcement practice followed different paths - that in order to deprive parental rights on this basis, a court verdict or a decree terminating the criminal case on non-rehabilitative grounds is required. In this situation, this in itself requires clarification, because non-rehabilitating grounds are different. Termination of a criminal case after the expiration of the term has long been a non-rehabilitative basis, and, nevertheless, it is impossible to say under such circumstances whether dad beat mom or mom beat dad. Therefore, here, it seems to me, another change will be made and it will be clarified exactly what grounds for terminating a criminal case are still grounds for saying that a crime has been committed.

Another point that the Supreme Court draws attention to. Deprivation of parental rights can be carried out in relation to the parent who controlled the situation

, that is, the circumstances that were the basis for deprivation of parental rights must depend on the actions of this parent. And for circumstances that do not depend on the actions of the parent, for example: mental disorder, chronic illness, with the exception of alcoholism and drug addiction - in these cases the parent is considered innocent in the circumstances that occurred and, accordingly, will not be deprived of parental rights.

The Supreme Court sidestepped the question of what to do with children whose parents are in prison. There are certain comments from the Supreme Court here that have been made elsewhere, in so-called responses to questions, when the Supreme Court clarifies certain provisions of the law on individual requests from the courts or on the fact that they analyze work practices. Under such circumstances, the position of the Supreme Court was expressed, but this issue was not reflected in this Resolution, and what to do with children whose parents are in prison, can they be deprived of parental rights or not - this question was not included in this Resolution of the Plenum not allowed in any way. Nevertheless, it is once again emphasized that the behavior of a parent, as a result of which he is deprived of parental rights, must necessarily be guilty

, and it was repeated several times that this is an extreme measure and is used in exceptional cases. We've heard this before. Actually, one of the basic understandings of deprivation of parental rights as a measure of parental responsibility has been preserved. And indeed, the Supreme Court considers deprivation of parental rights as a measure of parental responsibility. The concept of deprivation of parental rights as a measure of child protection finds its way into this issue quite slowly and, unfortunately, is not fully reflected in this Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court.